Introduction

On March 22, 2021, the Science and Ethics for Happiness and Well-being (SEH) initiative convened a virtual meeting to discuss the recently published World Happiness Report (WHR). The SEH working group welcomed editors and authors from the WHR team to present and discuss the results, methodology, and foundational assumptions of this year’s report, which focused on COVID-19 and well-being, including chapters on mental health, social connection, work, and the WELLBY approach for making happiness-based policy decisions. Below, we outline our discussion following the chapter presentations, emphasizing areas of agreement while also noting areas of debate and disagreement.

Inequalities of well-being during COVID-19

It was widely agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic has had profound adverse effects on society. Obvious impacts include disease and death, economic hardship, social isolation, and mental hardship (often in the form of anxieties or depression), and different countries had divergent economic and health outcomes based on cultural traits and, likely more importantly, stringent government policies.

It was also emphasized that no less important is the fact that these adverse effects have been felt differentially within societies. The pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated preexisting inequalities across race, gender, and class, and other dimensions, which we will discuss below.

Families and children

Families with children were more deeply stressed by the pandemic. First, the loss of in-person schooling constituted a real loss. Households with broadband connectivity were at an advantage, but parents were negatively impacted by increased challenges of balancing work and childcare. Mothers were more negatively impacted by fathers. Living with a partner, however, helped to increase people’s perception of their social connectedness and sense of belonging. Isolated individuals, on the other hand, had much greater psychological and practical burdens.

Mental

...

Read all

Introduction

On March 22, 2021, the Science and Ethics for Happiness and Well-being (SEH) initiative convened a virtual meeting to discuss the recently published World Happiness Report (WHR). The SEH working group welcomed editors and authors from the WHR team to present and discuss the results, methodology, and foundational assumptions of this year’s report, which focused on COVID-19 and well-being, including chapters on mental health, social connection, work, and the WELLBY approach for making happiness-based policy decisions. Below, we outline our discussion following the chapter presentations, emphasizing areas of agreement while also noting areas of debate and disagreement.

Inequalities of well-being during COVID-19

It was widely agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic has had profound adverse effects on society. Obvious impacts include disease and death, economic hardship, social isolation, and mental hardship (often in the form of anxieties or depression), and different countries had divergent economic and health outcomes based on cultural traits and, likely more importantly, stringent government policies.

It was also emphasized that no less important is the fact that these adverse effects have been felt differentially within societies. The pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated preexisting inequalities across race, gender, and class, and other dimensions, which we will discuss below.

Families and children

Families with children were more deeply stressed by the pandemic. First, the loss of in-person schooling constituted a real loss. Households with broadband connectivity were at an advantage, but parents were negatively impacted by increased challenges of balancing work and childcare. Mothers were more negatively impacted by fathers. Living with a partner, however, helped to increase people’s perception of their social connectedness and sense of belonging. Isolated individuals, on the other hand, had much greater psychological and practical burdens.

Mental health

The mental health impacts from the pandemic and control measures vary, and it is likely that we are only seeing the beginning of various impacts which will continue to unfold. Immediate impacts to mental health came due to fear of the virus and as a response to lockdown measures. Then there was a psychological impact due to short-term economic and social adversities wrought by the pandemic: Job loss, contracting the disease, changes in social contact, networks, and support, etc. But we should expect long-term psychological consequences to emerge as the result of economic recession and social unrest. We have yet to see the longer-term effects of the supply and demand effects of insufficient mental health support on psychological well-being.

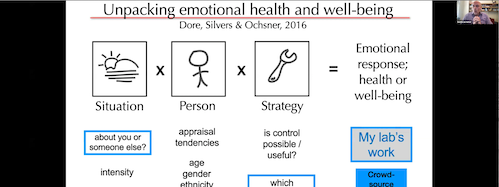

The pandemic had measurable initial negative effects on mental health in April and May of 2020, but by September 2020, however, there had been substantial recovery, with some persistent negative effects. Younger adults and women faced mental health challenges in particular. Younger adults reported being less happy in the beginning and they got worse. Older, happier adults report using reappraisal (i.e. looking on the bright side and finding adaptive meaning). Younger adults generally use suppression and hiding their feelings. But to the extent they use reappraisal, they are happier. Working women with children faced huge mental health challenges due to the burdens of child care.

Employment

Frontline workers (across healthcare, first responders, and essential services) have faced greater losses in quality of life. Healthcare workers faced incredible challenges due to increased work load, practical challenges, and risk of exposure to the virus. Other essential workers also faced health risks, and essential workers of marginalized ethnicities in urban areas faced social challenges as well.

The pandemic has reemphasized the importance of employment for happiness and well-being. Its effects on the labor market, however, have been highly unequal across different groups of workers. Low-income and low-skill workers faced higher risk of reduced working hours, thus exacerbating existing socioeconomic inequalities. The pandemic has widened intergenerational inequalities as well: Young workers faced significantly larger decline in employment rates compared to national averages. Finally, it was found that having social capital outside of work buffered the negative effects of unemployment, as did furlough status.

Methodological discussion: Life satisfaction and subjective well-being

Members of our group raised various interpretations to account for the general lack of change shown in subjective well-being measures during 2020, including the possibility that subjective well-being measures may not have reliably captured the decrease in quality of life many people experienced during the pandemic.

Some invoked resilience, our capacities to adjust, and other compensatory features to explain little change in self-reported life satisfaction. Others thought that resilience and grit are undertheorized phenomena that do not play an actual explanatory role, and they really just re-describe or rename the fact that there wasn’t much change in subjective well-being as measured by life evaluation reports. Others noted a social interpretation: You don’t feel as bad about your life being turned upside down if everyone else is having their life turned upside down too. This kind of thinking corresponds to suicide rates falling in most countries during WWII.

This conversation raised other methodological concerns about using subjective well-being measures. Some voiced concerns about the framing effect’s impact on people’s responses to subjective well-being. Wants and desires are constrained by social position and cultural factors, and so too are responses to the Cantril ladder questions. One would expect certain groups to report lower well-being based on their social positioning, but they do not. The concern was raised that using ‘resilience’ as an explanation of these populations’ ability to mitigate various inequalities may ultimately be misleading, a romanticizing of poverty and historic oppression. It diverts our attention away from the social construction of self-respect and well-being.

One participant noted the quick methodological elision from life satisfaction measures (i.e. Cantril ladder reports) to happiness. It was suggested that we consider combining life satisfaction with some emotional measures integrated over time, which might show more variability and specificity in peoples’ conditions and changes in conditions. Other questions were raised about the time orientation assumptions latent in the Cantril ladder questions.

All in all, our discussion seemed to indicate that, though everybody in our group agreed that life satisfaction measures are important and useful, there is disagreement on what and how important the limitations are. Indeed, among our group, happiness and well-being seem to be undertheorized.

Recommendations

First, we recommend that we return to the discussion of the foundations of happiness and well-being, including: subjective and objective conceptions of well-being; measurement problems; theoretical challenges; the development of more robust survey instruments; and the possibility of using indicators that combine objective and subjective components.

Second, more specifically, we recommend further discussing challenges of well-being inequality, across race, gender, class, and other dimensions. We need to more carefully look at the sharp comorbidities of ill-being across race and class especially.

Third, we recommend further discussion on the relevance of mental states and their creation to both theoretical conceptions of well-being and improving well-being outcomes. A critical investigation of the creation of mental states would also examine framing effects of life satisfaction self-reporting, focusing on framing effects on the poor and historically oppressed. Other relevant topics to investigate could include mind training and various domains of practical reasoning, both long celebrated by ethicists as being architectonic of well-being. The role of religion’s contributions to well-being also warrants further investigation, as does the phenomenological quality of being open to God or other forms of transcendence more generally.

Fourth, we recommend returning to the ethics of well-being outcome improvements. Should we prioritize well-being or the elimination of extreme ill-being? Should we prioritize improving well-being outcomes by helping people with problems that are non-adaptive rather than helping people with problems they can adapt to?

Finally, it was noted that most studies outlining the mental health effects of the pandemic focus on richer (and data-rich) countries, and on adults. We also recommend the need to procure evidence on mental health outcomes in a more diverse set of countries, and more data on the impacts of the pandemic on children, with a focus on changes in their educational experience.

Read Less