“Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice, for they shall be satisfied” (Mt 5:6)

On December 14, 2020, the Science and Ethics for Happiness and Well-being (SEH) initiative convened a virtual meeting to discuss Fratelli tutti, Pope Francis’ new encyclical on global fraternity. The encyclical is a call for the world to share in the common good on the basis of mutual friendship and a “love that transcends the boundaries of geography and distance.” Fratelli Tutti is a magnificent companion to Laudato Si’. The previous encyclical calls on humanity to protect the Creation, emphasizing that “Interdependence obliges us to think of one world with a common plan.” Fratelli Tutti urges us to create the universal brotherhood and sisterhood needed to achieve that common plan by finding new pathways to cooperation beyond our own communities and nations. This is a fitting message for a world that is rent by nationalism, ethnocentrism, and dangerous failures of global cooperation, even in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. SEH discussed the encyclical from the perspectives of ethics, psychology, neuroscience, and other disciplines.

Fratelli Tutti and the Thirst for Justice

Injustice wounds humanity. Human society urgently needs fairness, truth, social justice, and friendship, and we suffer deeply whenever injustice pervades human affairs. Jesus declares in the Beatitudes that those who hunger and thirst for justice, individually and socially, will be satisfied, already on Earth, albeit imperfectly, as a foretaste of the perfect realization of justice in Heaven. Fratelli Tutti, therefore, opens a path to beatitudo, happiness, by showing us how we can achieve justice at a scale that transcends material goods and extends to non-market goods such as climate, water, sun, biodiversity, friendship, fraternal love, good relations that seek the good of the other, education, values, “geography and distance.” We accomplish this by combining justice and mercy with a love for humanity

...

Read all

“Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice, for they shall be satisfied” (Mt 5:6)

On December 14, 2020, the Science and Ethics for Happiness and Well-being (SEH) initiative convened a virtual meeting to discuss Fratelli tutti, Pope Francis’ new encyclical on global fraternity. The encyclical is a call for the world to share in the common good on the basis of mutual friendship and a “love that transcends the boundaries of geography and distance.” Fratelli Tutti is a magnificent companion to Laudato Si’. The previous encyclical calls on humanity to protect the Creation, emphasizing that “Interdependence obliges us to think of one world with a common plan.” Fratelli Tutti urges us to create the universal brotherhood and sisterhood needed to achieve that common plan by finding new pathways to cooperation beyond our own communities and nations. This is a fitting message for a world that is rent by nationalism, ethnocentrism, and dangerous failures of global cooperation, even in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. SEH discussed the encyclical from the perspectives of ethics, psychology, neuroscience, and other disciplines.

Fratelli Tutti and the Thirst for Justice

Injustice wounds humanity. Human society urgently needs fairness, truth, social justice, and friendship, and we suffer deeply whenever injustice pervades human affairs. Jesus declares in the Beatitudes that those who hunger and thirst for justice, individually and socially, will be satisfied, already on Earth, albeit imperfectly, as a foretaste of the perfect realization of justice in Heaven. Fratelli Tutti, therefore, opens a path to beatitudo, happiness, by showing us how we can achieve justice at a scale that transcends material goods and extends to non-market goods such as climate, water, sun, biodiversity, friendship, fraternal love, good relations that seek the good of the other, education, values, “geography and distance.” We accomplish this by combining justice and mercy with a love for humanity that extends outward beyond all borders.

Major Themes of Fratelli Tutti

Fratelli Tutti is a call and a guide to doing good unto others in fraternity and friendship, justice and well-being, in a globalized world. The encyclical opens with a consideration of “certain trends in our world that hinder the development of universal fraternity.” These trends include the promotion of individual interest at the expense of the communitarian dimensions of life; limitless consumption and its accompanying throwaway culture; a loss of historical consciousness; insufficiently universal human rights (and a lack of recognition of universal human dignity); illusory social connection and digital communication; and information without wisdom.

Pope Francis offers the parable of the Good Samaritan as the central image of the encyclical. The story represents the great challenge of the pervasive “globalization of indifference.” Universal fraternity, for Pope Francis, is founded upon encountering the other beyond our own narrow community, recognizing his or her intrinsic transcendence, dignity and worth, and responding to this dignity by seeking and acting towards their well-being and the common good. The encyclical calls on us all to be “neighbors without borders.”

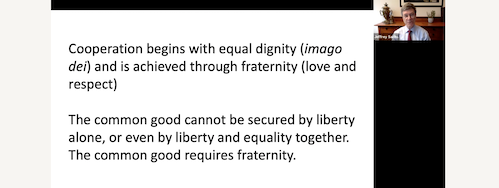

But how are we to develop and work towards such an open world? Fratelli Tutti suggests that we must reclaim our recognition of the vital importance of interdependence and sociality in making us who we are. Pope Francis calls for open societies that integrate and include everyone, that leave no one behind. He urges us to attend to the “‘hidden exiles’ who are currently mistreated as foreign bodies in society,” including the elderly, the disabled, the sick, the poor, and ethnic and racial minorities. For example, right at the beginning of the pandemic, Pope Francis, together with an important Statement by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and its friends, affirmed that the Covid-19 vaccine should be distributed to everyone, starting from the least among us. Pope Francis identifies solidarity based on mutual love as a crucial moral virtue for our time. To develop this virtue, we must re-envisage the social role of property and labor, starting with the recognition that “we have an obligation to ensure that every person lives with dignity and has sufficient opportunities for his or her integral development.” To achieve this, we must recognize that “the common use of created goods is the ‘first principle of the whole ethical and social order.’” Pope Francis also calls for us to move “beyond a world of ‘associates,’” in which we treat or use others as instruments for some particular good or advantage, to a universal fraternity that acknowledges the worth of every human person. Pope Francis suggests that authentic social dialogue produces real encounter, which in turn engenders fraternity. We cannot turn to false solutions to social and political conflict, such as war or the death penalty.

Obstacles to meaningful encounter and universal fraternity

The SEH core group identified several obstacles that subvert meaningful encounter and universal fraternity, and that must be addressed and overcome to achieve the vision of Fratelli Tutti.

First, at the individual level, not all people are equally capable of compassion. Our capacities for compassion vary across the “caring continuum,” and those at the very low end of the continuum tend to be responsible for a disproportionate amount of suffering. Our societies have been slow to recognize that dysfunctions in the brain circuits that support interpersonal care can cause psychopathy that can lead to great societal harms when afflicted individuals gain roles of leadership in government, the media, and other positions of authority.

Second, humans instinctively tend to extend their care and compassion preferentially for a small number of others – fratelli pochi rather than fratelli tutti. Favoritism plays a role here. More importantly, however, is the role of fear. Fear of the other and mistrust of others can impede our exhibition of extended compassion and care. Fratelli Tutti, extended brotherhood, must be cultivated as an individual virtue, and fostered at the level of society by reducing fears and building social trust.

A third obstacle to universal fraternity is racism, xenophobia, and stigma. Victims of racism, xenophobia, and stigma are less likely to feel like they belong. One cannot thrive (in school, at work, in life generally) unless each person is assured that they belong. Yet discrimination, whether by gender, race, religion, or other features of identity, deeply undermines that sense of belonging. Our communities and societies must accept, value and include all individuals as deserving of dignity. Racism and xenophobia prevent belonging and inhibit shared well-being.

Modern slavery, which SDG Target 8.7 intends to combat, is even worse, because its victims are not allowed to make their own destiny according to their dignity and freedom. Instead, they are subjected to mental and physical violence, whether in forced labor, prostitution or organ trafficking, whereas the body can only be given freely for love and cannot be bought or sold as a whole or in part.

Fourth, objective material hardships can render people less caring towards others. Those who are afraid about their future prospects or economic security may have less capacity for care. Yet the wealthy often develop a disdain for the rest of society, and engage in anti-social behaviors, while the poor demonstrate greater solidarity despite their material hardships. Economic inequality and social hierarchies prevent meaningful encounters that can bring about true integration. Mere contact does not constitute a meaningful encounter, as a meaningful encounter in general requires a meeting between equals.

Fifth, various social ideologies are obstacles to universal fraternity. Defenders of neoliberal dogma argue that positive spillovers on the poor of the free-market economy justifies the toleration of avarice, and even rename avarice as “entrepreneurship.” This ideology opposes direct redistribution for the poor and thereby tolerates unjust material suffering of the poor in the midst of great societal wealth. Another ideological source of resistance to a universal fraternity is the view that one’s obligation to share with others ends at the borders of one’s nation. Here we see the tension between the global and the local highlighted by Francis in Fratelli Tutti.

Pathways to Fraternity of All

To support an expanding circle of compassion, as inspired by Fratelli Tutti, we support the following actions.

We must undergird our support for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This moral charter of the UN affirms the dignity of all human beings and the universal rights to political, economic, civil, religious and social goods. As such, the UDHR can underpin universal fraternity. The UDHR is a crucial case of an “unforced consensus,” meaning that it offers a shared ethical bottom line across the world’s great ethical traditions, without requiring detailed agreement on precise philosophical, metaphysical, or religious foundations. As the UDHR reaches its 75th anniversary in 2023, the world should rededicate our efforts towards the realization of human rights, and update the UDHR to reflect 21st century human rights and responsibilities, including the right to a safe environment, digital privacy and security, and a world free of nuclear weapons and modern slavery.

The Sustainable Development Goals, agreed by all 193 UN member states, represents a practical set of goals by the year 2030 based firmly on the UDHR and universal human dignity, in line with Laudato Si’ and Fratelli Tutti. The SDGs, combined with the Paris Agreement on climate change, offer a practical step towards the “common plan” called for by Pope Francis.

We strongly concur with Fratelli Tutti that meaningful encounters can best be encouraged through dialogue, friendship, consensus building, and truth telling. Education – both secular and religious – and social infrastructure can be leveraged to foster openness, teach compassion and associated skills, and provide spaces for meaningful encounter, but especially for the greater good that is peace. Peace must be the ultimate goal of education. Pope Francis’s Global Pact on Education and the new Mission 4.7 of UNESCO, the Holy See, the Ban Ki-moon Foundation, and the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, aim to revolutionize education in the service of integral human development by encouraging education for sustainable development and global citizenship. As called for by SDG Target 4.7, education should foster a culture of peace and the provide the groundwork for an appreciation of cultural diversity. In light of this, intercultural and interreligious dialogue is key to adopting the universal truths and goods that distinct cultures have contributed to humanity.

We also emphasize the crucial importance of constructing a new framework of property rights based on the universal destination of goods, that is, upon a social ethic that ensures that all individuals can meet their basic economic needs. Such a new economic model, an Economy of Francesco, will incorporate insights from social psychology, which teach us that objective socioeconomic factors are important conditions of the possibility of both well-being and neighborliness (compassion, care, etc.). Pro-social norms (such as sharing, equality, honesty, compassion, common good, peacefulness) and social protection policies must play important roles in reducing fear, building trust, and promoting society-wide wellbeing.

Read Less